Common SQL queries through a non-1NF lens

For the past few months I’ve been working on “A modern guide to SQL JOINs” and some other book-related content. Today I’d like to discuss an alternative representation of some well-known SQL queries, such as LEFT JOIN and GROUP BY.

What if SQL allowed us to have nested datasets: entire tables inside column cells? From basic relational theory we know that this is a direct violation of the first normal form (1NF), but that’s fine, really.

Let’s see if that non-1NF intermediate representation helps us to better understand the underlying structure of common SQL queries. Here are the steps we’re going to take:

look at the classic SQL query;

express it in a hypothetical syntax that allows nested datasets;

canonicalize it back to the usual representation using a simple row duplication;

Sample dataset

We will use a sample dataset with two tables:

CREATE TABLE people (

id INTEGER NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY,

name VARCHAR(64) NOT NULL,

type VARCHAR(16) NOT NULL,

manager_id INTEGER NULL

);

CREATE TABLE payments (

id INTEGER NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY,

employee_id INTEGER NULL,

type VARCHAR(16) NOT NULL,

amount INTEGER NOT NULL,

date DATE NOT NULL,

description VARCHAR(64) NOT NULL

);

CREATE INDEX ndx_employee_id ON payments(employee_id);

Here is the playground URL: https://dbfiddle.uk/Y3Q4zRyw, where you can see some sample data inserted into those tables.

Example of non-1NF representation

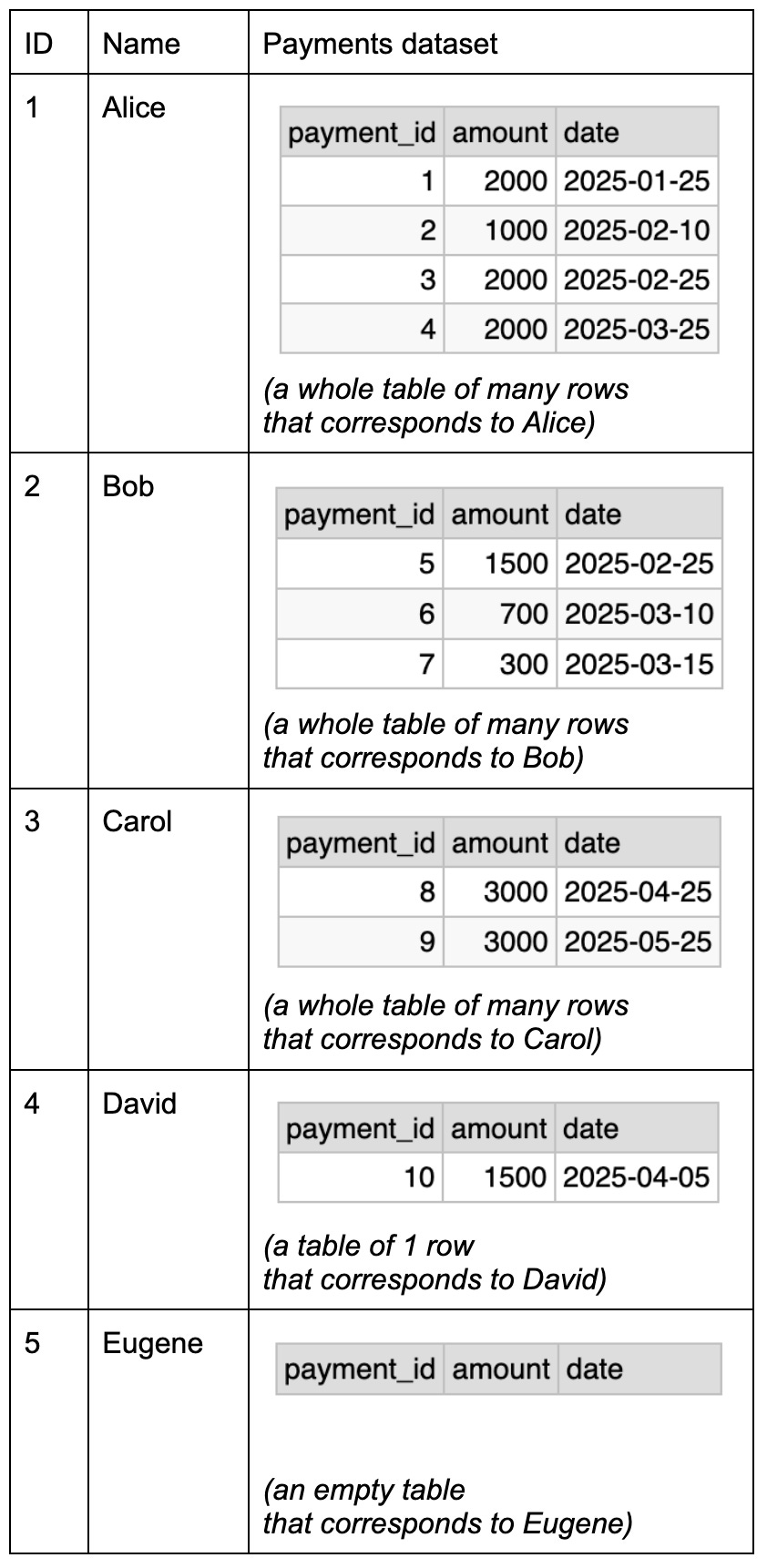

What is a non-1NF representation? Let’s pretend that it’s possible to have a dataset as a column type. It may look like this:

Undoubtedly, this is a 1NF violation. But it’s fine because this is only an intermediate representation.

To get a normal dataset from this intermediate representation, we will append outer rows to each of the inner rows, and gather them all together. That is, the outer row is duplicated as many times as there are rows in the inner dataset. If the inner dataset is empty, the outer row is skipped.

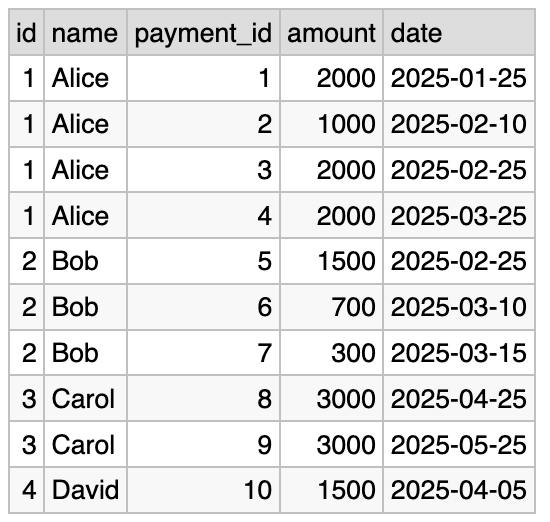

The canonical result looks familiar:

Here we have four copies of (1, Alice), three copies of (2, Bob), two copies of (3, Carol), one copy of (4, David), and no copies of (5, Eugene).

(The result actually corresponds to the INNER JOIN of people and payments.)

INNER JOIN

A normal SQL query for INNER JOIN is:

SELECT people.id,

people.name,

payments.id AS payment_id,

payments.amount,

payments.date

FROM people

INNER JOIN payments

ON people.id = payments.employee_id

SQL does not have a syntax for non-1NF representation, so we’ll invent a pseudo-syntax. Let’s just take two semicolon-separated queries: first is for the outer table, and second is for the inner dataset. The latter can access values from outer cells (in this example, ID and Name) using a special $outer identifier (again, a pseudo-syntax).

-- INNER JOIN (non-1NF)

-- outer query

SELECT id, name

FROM people;

-- inner dataset query

SELECT id AS payment_id,

amount,

date

FROM payments

WHERE employee_id = $outer.id;

LEFT JOIN

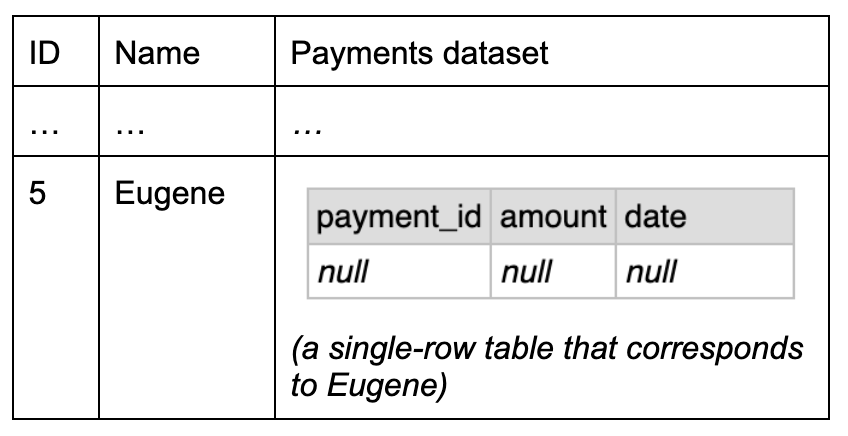

For the same input tables, LEFT JOIN would have just one difference for Eugene, who has no payments. Instead of an empty inner dataset we need to have a one-row dataset that consists entirely of NULLs.

We need to write an inner query such that if the normal result is empty, we replace it with a single hardcoded row.

For that we use basic algebraic core of SQL: EXISTS, UNION ALL and the constant row:

-- LEFT JOIN (non-1NF)

-- outer query

SELECT id, name

FROM people;

-- inner dataset query

SELECT id AS payment_id,

amount,

date

FROM payments

WHERE employee_id = $outer.id

UNION ALL

SELECT NULL, NULL, NULL

WHERE NOT EXISTS (

SELECT *

FROM payments

WHERE employee_id = $outer.id

);

(The “UNION ALL” part makes sure that there is always at least one row. Constant row is implemented by “SELECT NULL, NULL, NULL” without any table specification. In some databases you need to use the “DUAL” table name for that.)

Nice.

LEFT JOIN + GROUP BY

One last example:

SELECT people.id,

people.name,

COUNT(*) AS cnt

FROM people

LEFT JOIN payments

ON people.id = payments.employee_id

GROUP BY people.id, people.name

Could be represented by:

-- LEFT JOIN + GROUP BY (non-1NF)

-- outer query

SELECT id, name

FROM people;

-- inner dataset query

SELECT COUNT(*) AS cnt

FROM payments

WHERE employee_id = $outer.id

Here the inner dataset always contains a single row. This row has just one column that contains the number of payments (“cnt”).

What’s the point?

I want to see if this approach could help with teaching modern SQL. Admittedly, this requires an abstraction that is not described anywhere, even though it’s quite natural, in my opinion. Remember that it was literally the first thing that relational theory had to “normalize”.

But after you get used to it, notice how relatively simple the inner queries are in our three examples:

INNER JOIN is implemented by a filtered SELECT;

GROUP BY is implemented by an aggregated filtered SELECT;

famously awkward LEFT JOIN behaviour is implemented as a filtered SELECT and a UNION ALL with a NULL-only row, conditionally.

Nothing is special-cased.

In all cases you can say: here is what happens for each row of the first table, and study only the simpler inner part. A method of canonicalizing the result dataset is identical for any such representation. You can learn it once on a simple example, say for the GROUP BY, and then apply it to more complicated scenarios.

Exercise for an interested reader: implement correlated subqueries.

What’s next?

This is another experimental attempt at our general minimal modeling approach, this time applied to queries and not to datasets. The guiding belief here is that if you split a query into two simple parts, you may get back some of the thinking capacity.

We can experiment with this by applying it to a certain much bigger topic, but that’s for some other time.